Of all the desktop environments and window managers available on Linux, one has emerged as my favorite. Even though Xfce isn't as flashy as other desktops, I've come to rely on it.

One reason that I've stuck with Xfce is how few surprises it offers. When I first started using computers seriously, it was the Windows 3.x era. My first PC that I had at home run Windows 3.1. I would occasionally visit Macs that ran some variant of the OS, back when it was called "System" followed by a version number. The main version of what's now called "macOS" at the time was System 7 (macOS is now a lot closer to Linux under the hood, but that's another story).

I'm familiar with the desktop model, even though I'm more oriented towards the command line, which is also a consequence of having cut my teeth on MS-DOS. I could probably use something like a bare window manager or even a tiling manager, but I tend to feel vaguely uncomfortable. My first thought is, "How do I get out of this thing?" I suppose it's similar to people who can't figure out how to quit Vim. I know how Xfce works just by looking at it.

Why I'm Not Sold on Linux Tiling Window Managers

Sometimes it's better to stack (but I still tile when I want to).

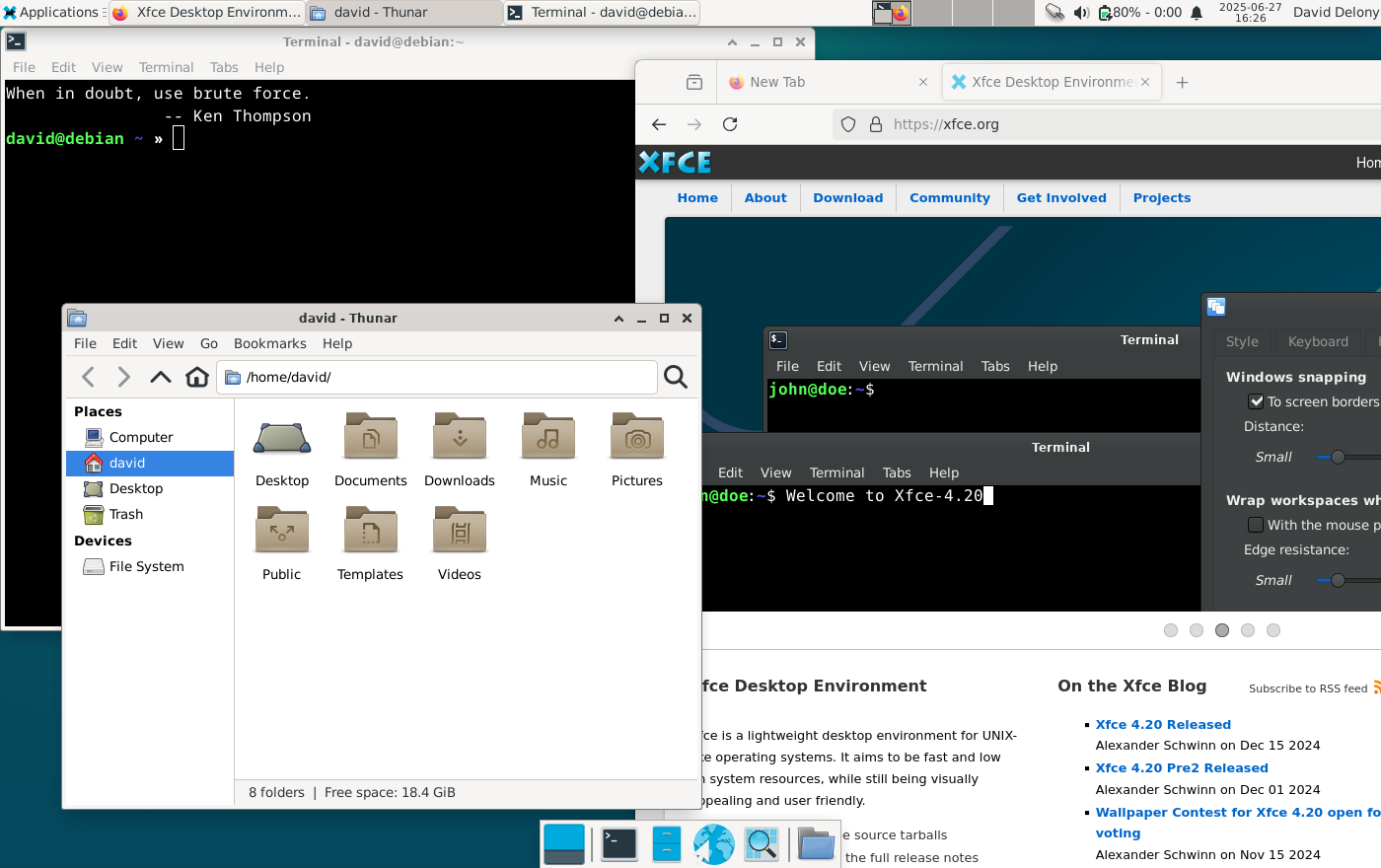

Xfce's embrace of the standard desktop model gives me a sense of comfort when navigating it, even if I haven't used the underlying OS. It's amazing that I can have a consistent environment that can follow me around across different operating systems. That's why Unix-like systems, including Linux, appeal to me so much.

As much as tech embraces change, on user interfaces, lots of people, including myself, are creatures of habit. They don't like it when developers move their cheese. Just look at any forum or subreddit whenever a major desktop announces some new change to the interface. Xfce has been remarkably consistent through the years I've used it.

4 Xfce Runs on Just About Anything

One thing that's always fascinated me about Linux and other Unix-like systems is how the user interface is decoupled from the underlying operating system. This is different from Windows or macOS. There, the graphical desktop is an integral part of the operating system. If something happens to it, the whole system goes down.

On Linux, the desktop is just another program. More accurately, it's just a collection of programs that run in layers. Xfce is ultimately just another program as well. Because it's open source and not tied to any particular operating system, it's been ported to just about everything under the sun. I've used it on Linux. I've used it on BSD. I've even used it on Tribblix, a descendent of OpenSolaris.

This shows Xfce's ubiquity. Chances are, if it exists, Xfce has been ported to it. I know I'll be able to use a desktop I'm familiar with.

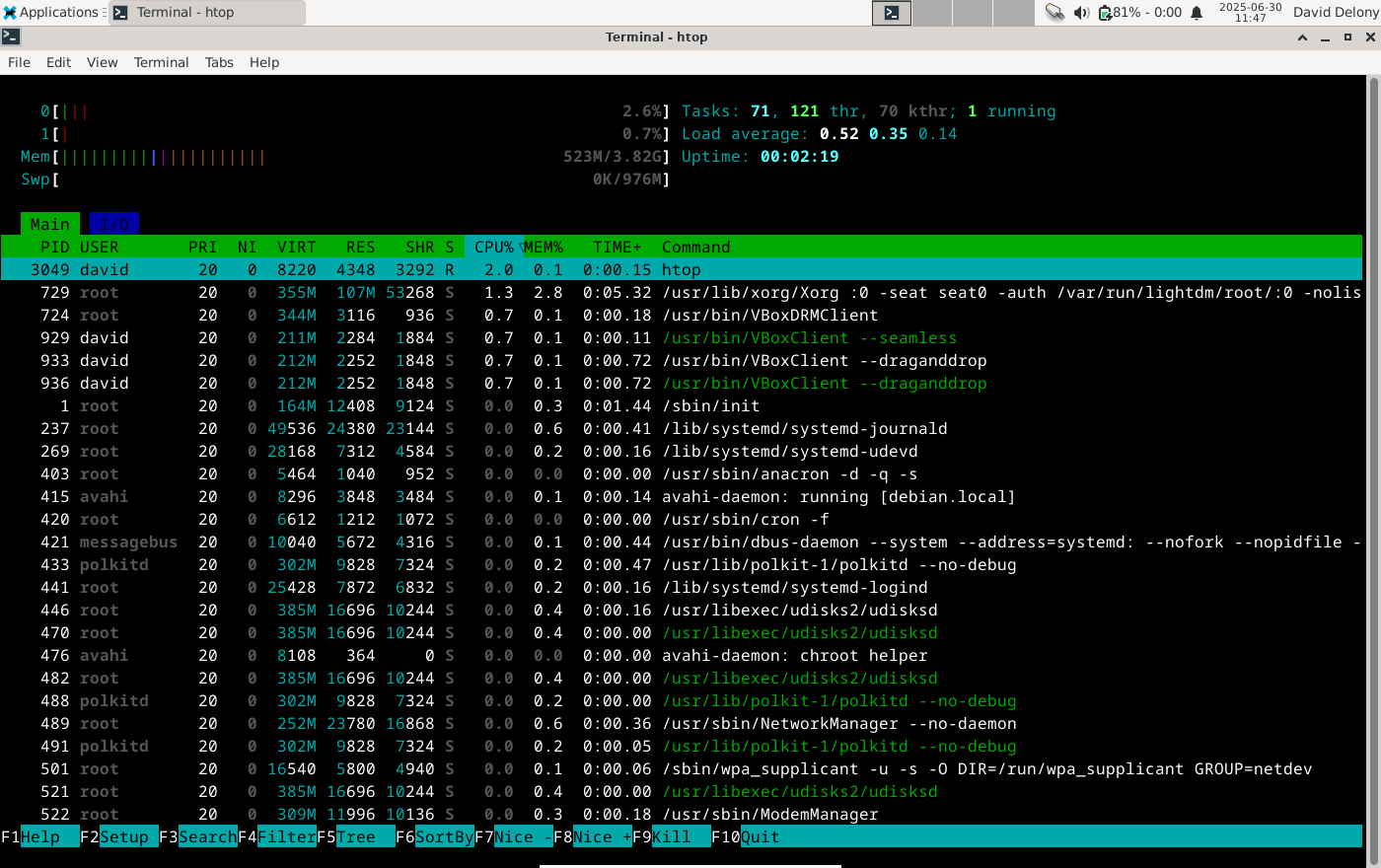

3 Xfce Has Low System Resource Usage

I test a lot of systems in my work for HTG. I don't have an endless supply of physical machines, so I rely on VirtualBox virtual machines for testing new Linux distros and other OSes. This is why I value Xfce's lightweight nature. It's lightweight in the sense that it doesn't require a great deal of resources. This is why it's my go-to for virtual machine desktops. I've also used it on low-power physical machines, like an old laptop.

Xfce is the default desktop on Raspberry Pi OS, formerly Raspbian, the Debian variant intended for use with the Raspberry Pi. It's also lightweight in that it doesn't attract attention to itself, which is something that I'll touch on later.

Xfce reminds me of the Amiga. The original (and still-going) AmigaOS was praised not only for offering nifty features that other consumer OSes didn't at the time, like multitasking, but also ran in 256KB of RAM, which was the base configuration of the original Commodore Amiga. As with the Amiga, Xfce shows you can pack some powerful features into the system.

2 I Can Tweak Xfce

While I like Xfce for having a simple desktop model, there's a lot more going on beneath the surface. Xfce is also very configurable. This is one of the explicit design goals for the project. According to Xfce's homepage, it's designed to be simple yet adheres to the "Unix Philosophy" of smaller programs that can be combined.

While Xfce has a pretty good panel layout of menus and other items like the system clock, I can configure and rearrange elements as much as I want to. I can swap out the standard application menu and replace it with the Whisker menu that lets me search the system the way I can on a Mac or Windows desktop. I can have a binary clock, in case I feel a tinge of regret for never being able to buy one from ThinkGeek in the 2000s.

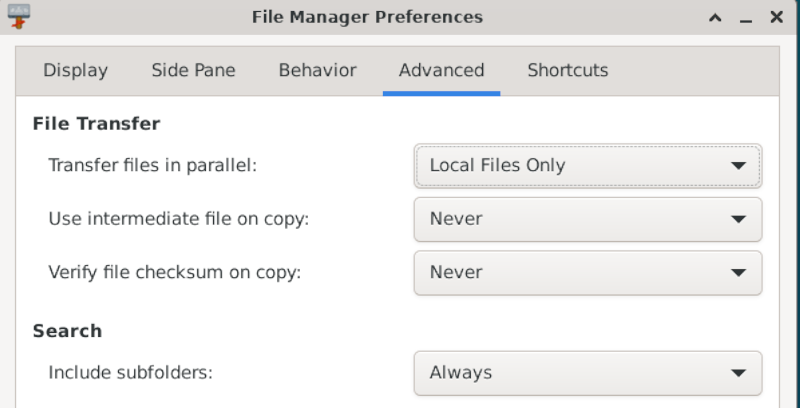

The system settings menus also offer some interesting tweaks. I can change things like the file icon size, but the "Advanced" tab lets me activate settings like transferring files in parallel. This shows how powerful the Xfce settings are in something this obscure. I like to think that like in NetHack, "the Xfce dev team thinks of everything."

I can even change the keyboard shortcuts. Xfce may appear simple on the surface, but there's a lot for users to change if they aren't happy with the defaults. Xfce represents the best balance in interface design: simple enough for novices but configurable for power users.

Xfce shows that "lightweight" doesn't have to mean "light on configurability."

1 Xfce Stays Out of the Way

One thing that I like about Xfce is that it doesn't seem to want to draw attention to itself. I remember using macOS and marveling at how windows would grow and shrink when they minimized or maximized.

You might also remember the Compiz plugin with the wobbly windows or the virtual desktop selection cube spin. I admit I thought that was cool, but now it's yet another thing I would be happy to leave in the 2000s.

When you minimize and maximize windows in Xfce, they just go to their new sizes. This seems like a deliberate design decision. It helps save on resource requirements, which makes Xfce popular on low-end machines.

Things like that seem fun at first, but animations and spinning just get in the way of what I'm trying to do. With Xfce, I can concentrate on the task at hand instead of marveling at some cool animation. I would rather marvel at writing some cool code or browsing some fun websites, or even playing a game. The interface can be aesthetically pleasing, but the Xfce developers seem to realize that it should be something you can ignore as well.

Xfce's simplicity is likely also a reason that it's been ported to just about every Unix-like system. A simpler desktop means that it can cope with a wider variety of hardware and it's less dependent on the underlying OS.

A lot of people criticize the slower release process, often with two years between releases, but sometimes, you don't want to mess with something that works. It seems the Xfce developers don't want to introduce features just to introduce features.

Xfce appeals to me because it offers the familiarity of a desktop with a design that is lightweight in terms of resources but also in general feel. It gets out of the way and lets me use the computer.